En janvier 2017, je me suis offert Bett, une importante foire mondiale pour la technologie éducative qui se tient à Londres annuellement au mois de janvier. S’y réunissent 850 compagnies, une centaine de Start-ups en edtech et plus de 30 000 visiteurs originaires de 130 pays et issus de la communauté mondiale de l’éducation.

On y présente les nouveautés en numérique éducatif. Bett se donne comme mission de rassembler les personnes, les idées et les pratiques afin que les éducateurs et les apprenants exploitent leur potentiel. C’est à Bett que je me suis intéressée, entre autres, à l’apprentissage de l’informatique par les élèves du Royaume Uni.

Au Royaume Uni

En septembre 2014, le Royaume Uni est devenu l’un des premiers pays du G9 à rendre l’apprentissage de l’informatique obligatoire dans ses écoles. L’informatique, matière obligatoire au Royaume Uni, un article paru dans le magazine École branchée à l’automne 2017, présente une synthèse du contenu des programmes d’études prescrits aux écoles primaire et au premier cycle du secondaire.

Je ne reviens aujourd’hui que sur quelques aspects de l’apprentissage de cette science au sein de laquelle se rencontrent machines et humains. Voici quelques extraits d’un atelier d’information que j’ai présenté à l’#accessedu qui se déroulait à l’Académie Lafontaine du 3 au 5 novembre dernier.

Les 3 aspects de l’apprentissage de l’informatique

Le National curriculum in England: computing programmes of study décline l’apprentissage de l’informatique selon trois aspects.

1- Computer science : informatique, algorithmique, programmation

2- Information Technology : les technologies de l’information, l’ordinateur et ses périphériques, les réseaux, les logiciels, les données et l’information

3- Digital Literacy : litéracie numérique, apprendre à vivre et à travailler dans le cyberspace

Le Computing at school (CAS)

Computing at school (CAS) a été créé en 2008 par quelques individus issus du milieu de l’industrie et des universités. Prenant conscience que les technologies de l’information telles qu’elles étaient enseignées n’intégraient pas la science informatique, ils ont souhaité faire quelque chose pour aider les enseignants qui désiraient enseigner l’informatique et encourager leurs élèves à entreprendre des carrières dans ce domaine. Ils ont créé CAS pour répondre à ce besoin. Leurs premières actions ont été de convaincre le Department for Education de l’importance de l’apprentissage de la science informatique par les élèves du Royaume Uni. CAS, organisme indépendant du gouvernement, est subventionné par l’industrie et a formé une alliance stratégique avec BCS, The Chartered Institute for IT, qui est l’association professionnelle des informaticiens du pays.

Le CAS dont l’accès est gratuit, compte maintenant plus de 20 000 membres et est présent dans 150 centres dans lesquels sont dispensées des formations au personnel enseignant. CAS a pour mission d’assurer un leadership pour soutenir les enseignants dans l’implantation du tout nouveau programme d’informatique. CAS publie des guides pédagogiques accessibles en ligne et fait la promotion du développement d’une pensée informatique chez les élèves.

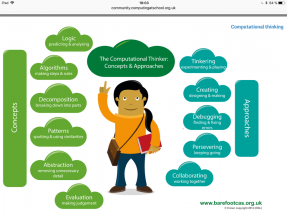

La pensée informatique

Le terme computational thinking a été utilisé la première fois par Seymour Papert en 1980. En français, on peut utiliser les deux termes : pensée computationnelle ou pensée informatique. Il s’agit du processus de pensée par lequel une personne formule un problème et exprime sa solution sous une forme qui peut être comprise par un ordinateur. C’est Jeanette Wing, dans un article de 2006, qui a exprimé que la pratique de la pensée informatique devrait être intégrée aux apprentissages de tous les écoliers dès la maternelle.

Il n’y a pas consensus sur la définition donnée à la pensée informatique. La définition en traduction libre qui précède est celle préconisée par le CAS.

Quelques réflexions personnelles

Que ce soit dans trois ou cinq ans, je fais le pari que l’apprentissage de la science informatique sera obligatoire dans les écoles du Québec.

L’idée selon laquelle l’implantation du programme doit se faire par l’entremise d’un (ou des) organisme(s) indépendant(s) du gouvernement est à considérer. Cette forme permettrait d’assurer que cet enseignement soit indépendant des politiques et des budgets gouvernementaux.

Rendre le programme obligatoire ne signifie pas nécessairement d’exiger l’enseignement par tous les enseignants. Je propose ici une analogie entre le développement de l’implantation de ces nouveaux programmes et le gel d’un lac. Le lac ne gèle pas en un seul bloc, mais plutôt par le développement de cristaux de glace qui s’assemblent graduellement. Après un certain temps, si les conditions sont favorables, le lac devient entièrement gelé.