Par Jacinthe Ruel, conseillère en transfert et innovation en éducation au Centre de transfert pour la réussite éducative du Québec (CTREQ), Alain Poirier, consultant en éducation et accompagnateur CAR, et Amélie Roy, conseillère en transfert et innovation en éducation au CTREQ.

Dans cet article présentant les apprentissages du projet CAR : collaborer, apprendre, réussir, il est question des travaux des communautés d’apprentissage professionnelles (CAP) qui permettent de répondre à la question : Que voulons-nous que nos élèves apprennent?

Dans un précédent article, il a été question du projet CAR : collaborer, apprendre, réussir, un mouvement auquel participent une soixantaine de centres de services scolaires (CSS) et commissions scolaires (CS) au Québec, et qui soutient le développement d’approches collaboratives visant la réussite de tous les élèves[1]. L’un des moyens de collaboration privilégiés dans le cadre de CAR est celui de la communauté d’apprentissage professionnelle (CAP).

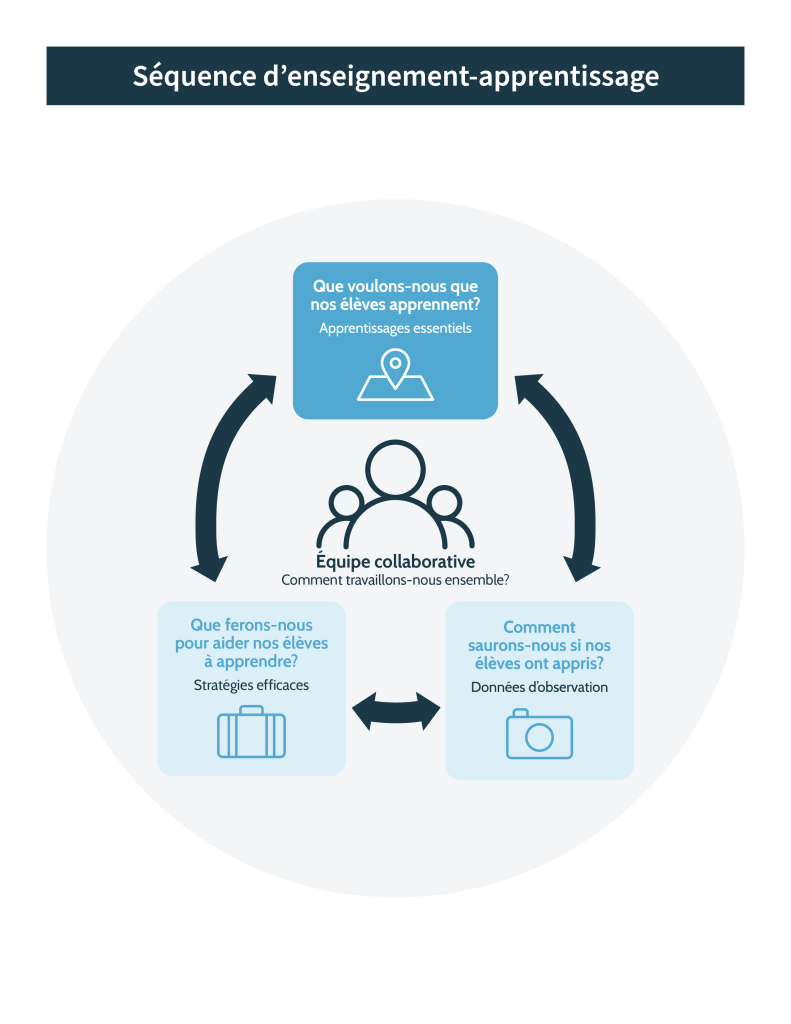

Dans une école qui fonctionne en CAP, les membres du personnel scolaire, regroupés en équipes collaboratives selon les niveaux, les matières ou les cycles, travaillent ensemble de façon systématique pour améliorer les pratiques pédagogiques et la réussite des élèves en répondant à trois questions clés :

- Que voulons-nous que nos élèves apprennent?

- Comment saurons-nous si nos élèves ont appris?

- Que ferons-nous pour aider nos élèves à apprendre?[2]

Dans une série de trois articles intitulée « La CAP en action! », nous approfondirons le processus de travail de ces équipes collaboratives centrées sur l’apprentissage.

Dans une école qui fonctionne en CAP, les membres des équipes collaboratives travaillent à l’atteinte d’un but commun : la réussite de tous les élèves. Les enseignants, les orthopédagogues, les directions et les conseillers pédagogiques se rencontrent régulièrement pour :

- Cibler les apprentissages essentiels (prioritaires) à réaliser par les élèves (Que voulons-nous que nos élèves apprennent?);

- Analyser les données d’observation qu’ils recueillent pour suivre le progrès des élèves (Comment saurons-nous si nos élèves ont appris?);

- Prendre des décisions pédagogiques en s’appuyant sur ces données et sur des résultats de recherche pour mettre en œuvre les stratégies d’enseignement les plus efficaces (Que ferons-nous pour aider nos élèves à apprendre?).

Ce processus de travail se réalise souvent dans le cadre d’une séquence d’enseignement-apprentissage (voir le schéma ci-dessous). Le présent article porte sur la première question CAP : Que voulons-nous que nos élèves apprennent?[3].

Apprentissages essentiels

Que voulons-nous que nos élèves apprennent? Voilà la première question à laquelle les membres de l’équipe collaborative cherchent à répondre. Bien que les différents contenus du programme de formation continuent d’être enseignés, les enseignants et les professionnels déterminent les apprentissages « essentiels », c’est-à-dire ceux qui sont jugés prioritaires pour faire l’objet d’un suivi systématique et de discussions lors de leurs rencontres collaboratives.

Les apprentissages prioritaires sont reliés aux objectifs du projet éducatif et posent un défi dominant aux élèves. Ils sont aussi priorisés parce qu’ils sont préalables (doivent être acquis pour un passage au niveau supérieur), transférables (utiles dans d’autres matières scolaires ou disciplines) et durables (susceptibles d’être réinvestis à court ou moyen terme)[4].

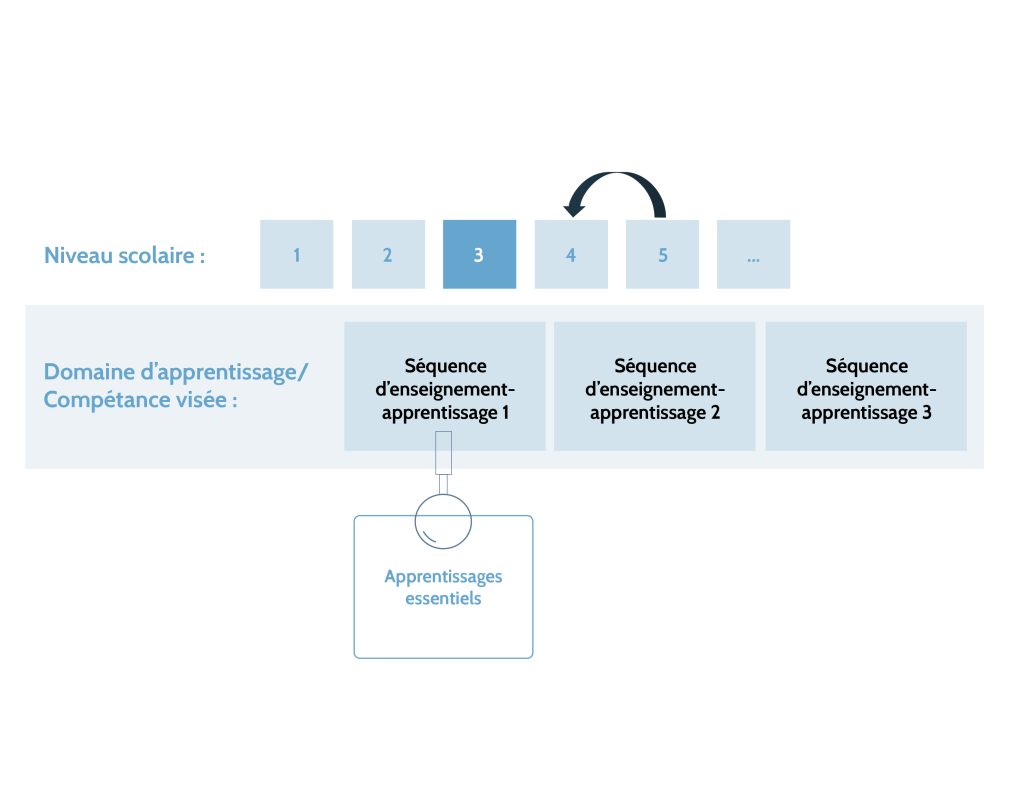

Le travail des équipes collaboratives qui forment la CAP peut se réaliser de différentes façons, notamment par la mise en œuvre de séquences d’enseignement-apprentissage dont la durée est généralement de quelques semaines. Pour chaque séquence, les membres de l’équipe ciblent un nombre limité d’apprentissages prioritaires logiquement reliés qui seront abordés « ensemble » pendant la période visée et qui feront l’objet d’un suivi systématique.

Tout au long de la séquence, les enseignants recueillent auprès des élèves des données d’observation (preuves de l’apprentissage) afin de suivre le progrès réalisé et d’ajuster leur enseignement en utilisant les stratégies les plus prometteuses. À la fin de la période visée, les apprentissages ciblés sont évalués et des modifications sont apportées à la séquence qui peut ainsi se développer et s’enrichir au fil du temps.

Planification globale des apprentissages

La planification d’une séquence d’enseignement-apprentissage est un processus dynamique et itératif qui est évidemment relié à une planification plus globale du parcours d’apprentissage des élèves. Par exemple, pour déterminer de façon cohérente les apprentissages à réaliser dans une séquence en particulier, les membres de l’équipe collaborative doivent avoir une compréhension claire de ce que les élèves devraient avoir appris à la fin de l’année scolaire pour un niveau donné. Et pour avoir une compréhension claire et partagée de ce qui doit être enseigné et appris à chaque niveau scolaire, il doit y avoir une concertation entre tous les membres de l’équipe-école.

À partir des éléments contenus dans les documents de référence à leur disposition (p. ex. : attentes de fin de cycle du PFEQ, indications dans la Progression des apprentissages, guides professionnels appuyés par la recherche), les enseignants précisent ce qui doit être appris à la fin de la 6e année du primaire ou de la 5e secondaire, ce qui leur permettra de déterminer par la suite ce qui doit être appris aux niveaux précédents. Cette planification dite à rebours, lorsqu’elle est effectuée collectivement, favorise la mise en œuvre réaliste et harmonisée du programme et permet aux élèves de cheminer de façon cohérente à travers leur parcours scolaire, peu importe l’enseignant.

À titre d’exemple, la planification d’une séquence en 3e année du primaire tiendra compte non seulement des exigences de ce niveau scolaire, mais aussi des attentes aux niveaux qui précèdent et qui suivent :

Cibles, niveaux de réussite et évaluation commune

Les membres de l’équipe collaborative précisent les cibles d’apprentissage et les niveaux de réussite qui leur permettront d’apprécier le progrès des élèves tout au long de la séquence d’enseignement-apprentissage. Les cibles d’apprentissage correspondent à ce que les élèves doivent savoir, être capables de faire, comprendre et communiquer, de façon plus précise, relativement à chaque apprentissage priorisé. Elles sont formulées dans un langage clair pour qu’elles soient compréhensibles aux élèves. Les cibles doivent aussi être réalistes, observables et atteignables dans la période prévue pour enseigner et réaliser les apprentissages.

Pour chacune des cibles, les membres de l’équipe établissent les niveaux de réussite qui sont souvent associés à un système de couleurs : le vert indiquant l’atteinte de la cible, le jaune dénotant des difficultés à l’atteindre et le rouge signalant que la cible n’a pas été atteinte, par exemple. L’évaluation de l’atteinte des cibles se fait en classe par le biais de tâches d’évaluation communes qui correspondent à ce qui a été enseigné (p. ex. : un mini test ou un entretien de lecture), de même qu’à partir d’outils d’observation qui permettent de recueillir des preuves de l’apprentissage (p. ex. : grille d’observation).

C’est ensuite en discutant de travaux d’élèves qui sont représentatifs du niveau de réussite visé et de travaux qui se situent sous les attentes ou qui les dépassent que les membres de l’équipe collaborative développent une compréhension partagée du cheminement possible des élèves face aux apprentissages à réaliser. Cette compréhension des étapes de progression est, selon le chercheur John Hattie, un facteur clé de réussite dans les écoles[5].

Communication claire des cibles aux élèves

Finalement, il importe que les cibles d’apprentissage soient communiquées de manière explicite aux élèves et qu’elles leur soient rappelées fréquemment. Au primaire, par exemple, les cibles peuvent être affichées dans la classe et mentionnées au début des périodes de travail. Au secondaire, plusieurs enseignants remettent des grilles d’évaluation simplifiées dès le début du processus d’apprentissage. Dans plusieurs cas, on présente un ou des exemples de productions attendues afin que les élèves sachent ce vers quoi ils doivent tendre pour réussir et qu’ils soient mieux outillés pour juger de leur progression et réguler leurs propres apprentissages.

Conclusion

À ce stade du processus de travail en CAP, la collaboration soutenue des membres de l’équipe favorise la clarté et la cohérence quant à la compréhension des apprentissages qui auront le plus d’incidence sur les élèves et à la façon dont ces apprentissages seront mesurés.

Ne manquez pas le prochain article de la série « La CAP en action! » qui portera sur le processus de suivi du progrès des élèves. Nous y verrons que ce processus de suivi, appuyé sur des preuves d’apprentissage, est la clé du succès des CAP les plus performantes.[6]

Lire aussi dans l’École branchée :

Visionnez la vidéo « Travailler en CAP : Que voulons-nous que nos élèves apprennent? ». Consultez la Fiche de visionnement de la vidéo sur le site Web CAR pour animer une réflexion collective avec les membres de votre équipe-école.

Références dans le texte

[1] Voir Poirier et Roy (2022a).

[2] Pour une explication détaillée des fondements du travail en CAP, voir Poirier et Roy (2022b).

[3] Cet article s’appuie largement sur la page dédiée aux apprentissages essentiels sur le Site Web CAR : http://projetcar.ctreq.qc.ca/apprentissages-essentiels/

[4] Leclerc (2012) parle de rétention (réinvestissement de l’apprentissage à moyen et long terme), transfert (apprentissage applicable dans d’autres domaines) et préalable (apprentissage qui prépare pour la suite) pour distinguer les apprentissages qui sont essentiels (p. 154). Voir aussi Dufour et al., 2019, pp. 125-127.

[5] Hattie (2017), cité dans DuFour et al., 2019, p. 131.

[6] Leclerc, 2012, p. 32.

Références

- Centre de transfert pour la réussite éducative du Québec [CTREQ]. (2018). Apprentissages essentiels. Que voulons-nous que nos élèves apprennent? CAR : collaborer, apprendre, réussir. http://projetcar.ctreq.qc.ca/apprentissages-essentiels/

- Dufour, R., DuFour, R., Eaker, R., Many, T. W., et Mattos, M. (2019). Apprendre par l’action. Manuel d’implantation des communautés d’apprentissage professionnelles (3e éd.). Presses de l’Université du Québec.

- Leclerc, M. (2012). Communauté d’apprentissage professionnelle. Guide à l’intention des leaders scolaires. Presses de l’Université du Québec.

- Poirier, A., et Roy, A. (2022a). Projet CAR : collaborer, apprendre, réussir ! École branchée : enseigner à l’ère du numérique. https://ecolebranchee.com/projet-car-collaborer-apprendre-reussir/

- Poirier, A., et Roy, A. (2022b). Travailler en CAP, ça veut dire quoi? École branchée : enseigner à l’ère du numérique. https://ecolebranchee.com/travailler-en-cap-ca-veut-dire-quoi/