L’Association for Psychological Science (APS) publiait recemment les résultats d’une recherche sur le bilinguisme menée par des chercheurs de l’Université Western Ontario. Cette étude démontre que le bilinguisme ne présente pas d’avantages cognitifs significatifs.

On conviendra qu’être bilingue permet aux gens de multiples possibilités. Entre autres, il est plus facile de se trouver un emploi et de le pratiquer. Parler une autre langue pour voyager dans d’autres pays est aussi très utile. Socialement, les personnes bilingues peuvent multiplier leurs interactions avec les autres (amis, clients, collègues…). Être bilingue élargit l’accès à l’information, au loisir, au divertissement.

On peut aussi supposer que le bilinguisme ou le plurilinguisme offre des avantages cognitifs. Les fonctions exécutives des gens bilingues seraient-elles plus efficaces? Les liens cérébraux des jeunes ayant un trouble de l’attention seraient-ils plus fluides en apprenant une deuxième langue? Le bilinguisme pourrait-il avoir un effet de protection cognitive en vieillissant et retarder ou combattre certains dysfonctionnements du cerveau (la démence, par exemple)?

Une équipe de chercheurs de l’Université Western Ontario s’est penchée sur ces suppositions. Ils ont remarqué que les études précédentes sur le lien entre le bilinguisme et les fonctions cognitives démontraient différents résultats. Elles se contredisaient souvent ou bien leur validité était remise en question. Basées parfois sur de petits échantillonnages, ces recherches auraient été biaisées par des facteurs qui influencent les données, tels que la situation socioéconomique, la provenance géographique des sujets et leur éducation. Ils ont aussi remarqué que les études soutenant la théorie des avantages du bilinguisme étaient plus susceptibles d’être publiées en articles complets que celles qui concluaient à l’hypothèse nulle ou à l’avantage aux gens monolingues, ce qui remet en doute la validité de ces publications.

Une étude menée auprès de plus de 11 000 volontaires

L’équipe ontarienne a donc procédé à une nouvelle étude en basant sa recherche sur 11 041 participants âgés entre 18 et 87 ans. Pour réussir à obtenir autant de participants, l’étude a été faite en ligne. Selon les chercheurs, Internet offre une belle occasion d’examiner la relation entre le bilinguisme et les fonctions exécutives dans la population en général. Le large éventail de participants présentait une variété de facteurs sociodémographiques nécessaires à l’étude (langues parlées, situation socioéconomique, pays de naissance, éducation, etc.).

L’analyse a permis de comparer un échantillonnage de sujets présentant des portraits similaires (ou appariés), mais séparés en deux sous-groupes, l’un étant monolingue et l’autre, bilingue. Un autre échantillon étudié présentait des facteurs plus aléatoires pour les deux sous-groupes linguistiques. C’est à l’aide des réponses aux questions sociodémographiques que l’équipe a pu classer les sujets.

Les participants avaient ensuite à compléter 12 tâches cognitives dont les données étaient recueillies par la plateforme en ligne Cambridge Brain Sciences. Ces tâches permettaient d’évaluer l’inhibition, les fonctions exécutives, l’attention sélective, le raisonnement, la mémoire à court terme verbale, la mémoire de travail spatiale, la planification, la flexibilité cognitive. Chacune de ces tâches était analysée à partir de trois facteurs : le raisonnement, les habiletés verbales et la mémoire.

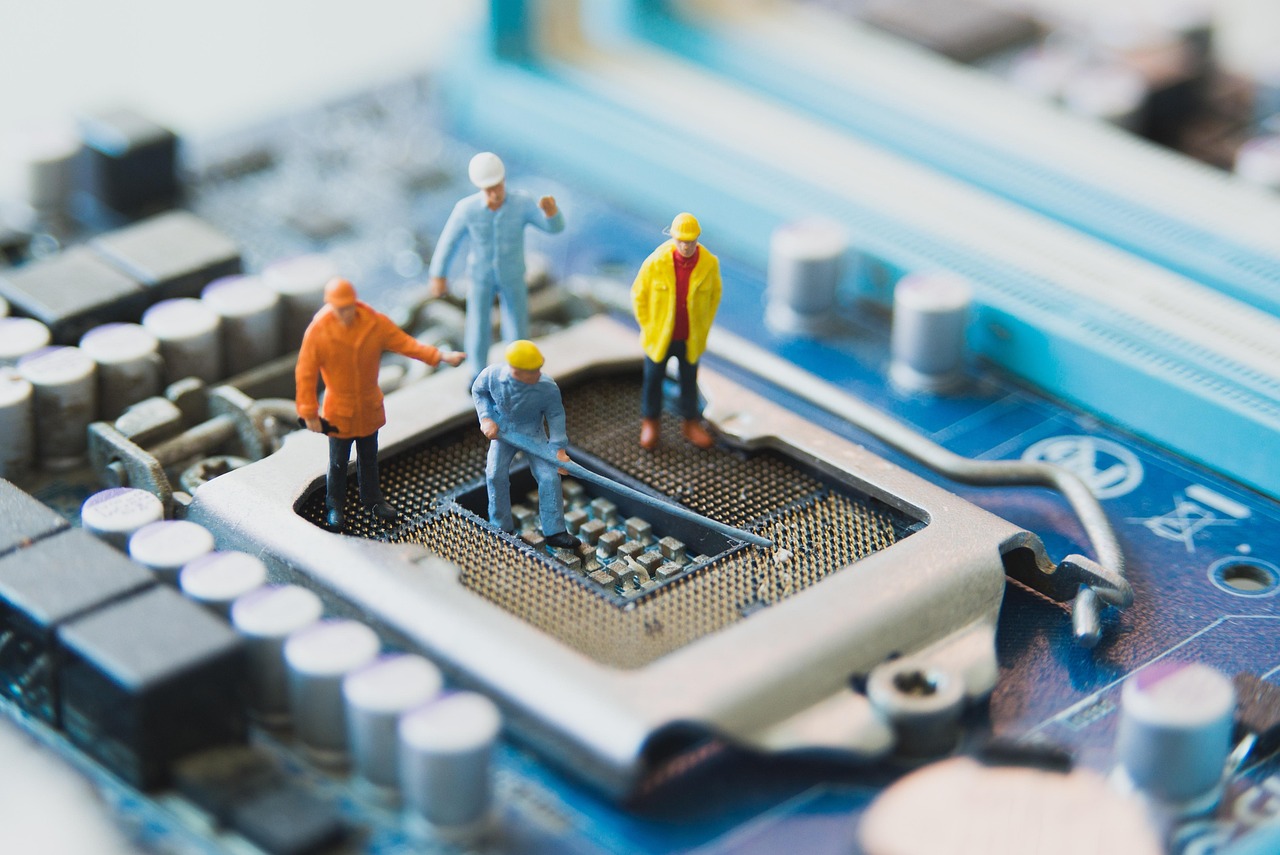

L’aide précieuse d’outils technologiques pour l’analyse de grands échantillons

Grâce aux outils technologiques disponibles aujourd’hui, l’analyse de résultats d’un grand échantillonnage est envisageable. Calculer les résultats des douze tests en tenant compte des trois facteurs et des situations sociodémographiques de chacun des 11 041 participants est un travail beaucoup trop colossal pour cinq chercheurs. Toutefois, quand l’ordinateur recueille les données, les pousse dans les calculs matriciels et crée les graphiques pour les analyser, l’étude à grande échelle devient possible. Ainsi, la validité de la recherche est aussi plus susceptible d’éliminer les erreurs.

Une étude de type observationnelle

Il est à noter, cependant, que l’étude est dite observationelle puisque les données ont été recueillies auprès de volontaires qui se sont auto-sélectionnés et n’ont pas été assignés au hasard à des groupes. L’approche de cette recherche était d’examiner la relation statistique complexe entre la performance aux tâches cognitives et les changements de l’activité cérébrale afin de saisir leurs influences mutuelles.

Suite à l’analyse des données, le groupe de chercheurs conclut que les résultats aux douze tâches cognitives ne montrent pas d’écarts significatifs entre les gens bilingues et ceux qui sont monolingues. Partout où les résultats diffèrent, l’écart est très mince, même pour le facteur de l’âge, et demeurent négligeables. L’hypothèse nulle de l’avantage cognitif pour les gens bilingues est donc révélée par cette étude.

Malgré le fait qu’être bilingue n’est pas un avantage pour les fonctions cérébrales, les bénéfices sociaux et personnels à parler deux ou plusieurs langues sont, et resteront toujours, considérables.