This article is part of

Vol. 1, issue 1 (Fall 2021)

of EngagED Learning magazine.

A simple matrix based on the organizational culture

By Jacques Cool, Education consultant (@zecool)

and Maxime Pelchat, Digital strategist (@mxpelchat)

CADRE21

One element that the pandemic seems to have brought to light is the need, for those working in the educational sector, to maintain professional development and enable them to keep current on new teaching realities, approaches, educational strategies and resources that may include online learning.

Professional development remains an integral part of any professional’s career path.

Over time, what a teacher and other professionals learned at university during their education is now only the basis for learning and mastering professional knowledge during their career. The question is therefore to identify the “where”, the “when” and the “how” to ensure this professional development.

Maurice Tardif, 2018

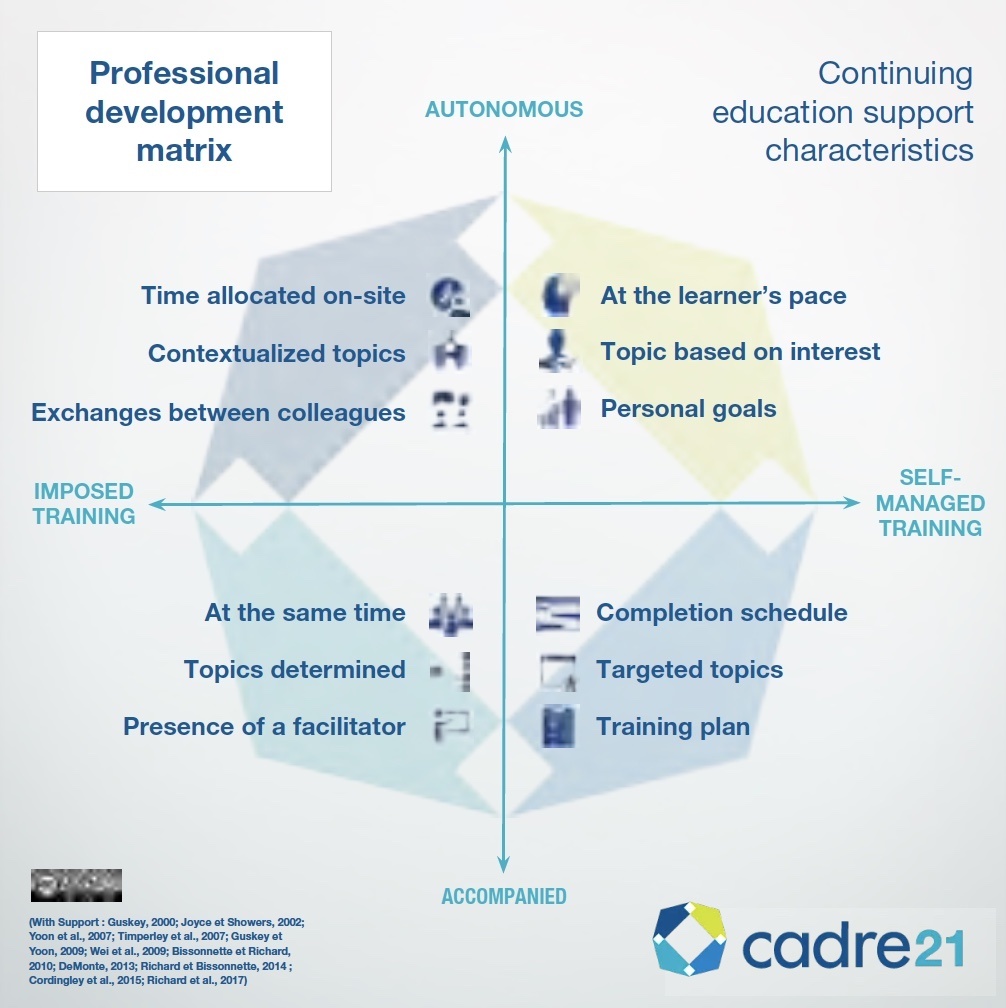

The team at CADRE21 (cadre21.org) has developed a professional development matrix (Figure 1) that enables different stakeholders to identify a variety of forms of support, while respecting their communities’ existing conditions and organizational culture. This aspect appears vital: when it comes to professional development, each setting’s conditions will often dictate the level of individual or collective commitment.

The timing, the topic discussed and the objective pursued help determine what form of professional development to pursue. The matrix has four quadrants that are based on the type of support to be provided to the professional as well as the implementation framework associated with the professional development activity.

Contextualize the matrix in your environment

Here are four cases observed in various regions of Québec over recent years that help materialize each of the quadrants.

Open topics, with support and collaboration

POSSIBLE ACTIONS

- Organize it during a pedagogical day with open topics

- Foster collaboration and co-development

- Adapt your support practices to the needs of teachers

- Increase teachers’ sense of professional effectiveness

At the Centre de services scolaire de la Pointe-de-l’Île, in the Montréal region, the leadership of the information technology (IT) services team was instrumental in enabling a very large number of teachers to explore the online self-study offer, in particular those of CADRE21 and of RÉCIT. By facilitating these exploration sessions with school teams, while modeling a commitment to their training, the IT services team was able to educate teachers about the possibilities of continuing education via digital technology. This strategy has helped to increase the sense of professional effectiveness.

Topic according to a need, facilitated locally, with staff mobilization

POSSIBLE ACTIONS

- Plan it during an educational half-day

- Select topic based on a common need

- Facilitate using a flipped classroom approach

- Push the group to analyze practices

At the Antoine-Manseau primary school in Joliette, the continuing education priority for all educational staff was established collectively and targeted the issues of sound classroom management. Based on reflections undertaken in a large group, each teacher was then able to pursue a process of reflective action (“I experiment and I reflect on my practice”) around this topic. Various forms of support were provided over a given period of time, allowing for helpful objectification, both individual and collective.

Everyone has their own pace and their own goals

POSSIBLE ACTIONS

- Differentiate means to meet continuing education needs

- Make it conducive to a good work-family balance

- Give possibilities of diversified support practices

- Promote knowledge transfer to class

The education community is notably made up of “vectors” of good resources, in its environment (resource teachers, educational consultants), in informal networks (social networks through hashtags such as #profdev, #teacherPD, #continuingeducation or #ChangeEvaluation) or within organizations and professional associations whose mission is the continuing education of members. The example of CréaCamp’s activities should be noted: An expert facilitator who enables any learner to get started and try, even get involved in a community of practice, then reinvest in their environment and potentially move on to the next one. Basically, each learner is responsible to commit their time and energy.

Collective game plan, with the time required to get there

POSSIBLE ACTIONS

- Make it a central element of an institution’s PD catalog

- Offer flexibility within an established team framework

- Determine general indicators of success

- Base learner’s commitment on their continuing education needs

The example of the dynamic put in place over the past year at Shrebrooke’s Le Salésien school is interesting. The educational leaders of this secondary school mobilized their teachers around a shift towards flexible teaching spaces development, primarily from a pedagogical perspective. Training time was provided to each teacher and it was up to each one to perfect their knowledge on the subject while embarking on a process of gradually integrating it into their practices. The feedback provided to these teachers remains a major pivot for more sustainable professional learning.

A well-rounded professional development offer

In Québec, “continuous education for teachers also engages the responsibility of school administrators, educational organizations, unions, universities and the Ministry, which implemented the conditions required to make it easier for practicing teachers to participate.” (Reference document, page 75)

The matrix presented here is intended to illustrate the variety of “conditions necessary to facilitate participation” implemented locally. Against a background of valuing and recognizing the new professional skills developed, this “leadership effect” becomes a significant lever for a greater “teacher effect”. And, at the end of the day, it is the youth who benefit.

References

Ministère de l’Éducation du Québec. Référentiel de compétences professionnelles – Profession enseignante. Accessed online on May 25, 2021: https://cdn-contenu.Québec.ca/cdn-contenu/adm/min/education/publications-adm/devenir-enseignant/referentiel_competences_professionnelles_profession_enseignante.pdf

Tardif, M. (2018). Travailler sur des êtres humains : objet du travail et développement professionnel. Dans J. Mukamurera, J.-F. Desbiens et T. Perez-Roux (dir.), Se développer comme professionnel dans les professions adressées à autrui (p. 31-62). Montréal (Québec) : Éditions JFD inc.

Uwamariya, A. et Mukamurera, J. (2005). Le concept de « développement professionnel » en enseignement : approches théoriques. Revue des sciences de l’éducation, 31(1), 133–155.